Optimizing Revenue with Subscriptions and Ads

Hello friends,

Welcome to a fresh edition of Growth Croissant.

So far, our CLV discussions have focused on paid subscriptions. Many consumer products also monetize via advertising, either as a primary source of revenue or complementary to subscription revenue.

Let’s explore the different types of ads, the pros and cons of different approaches, and some important considerations when mixing ads and subscription revenue. By sharing some of the stuff we’ve learned, I hope you develop a framework for how to best monetize your business.

Disclaimer: the post below (and the Croissant generally) reflects my views only.

A mixed bag

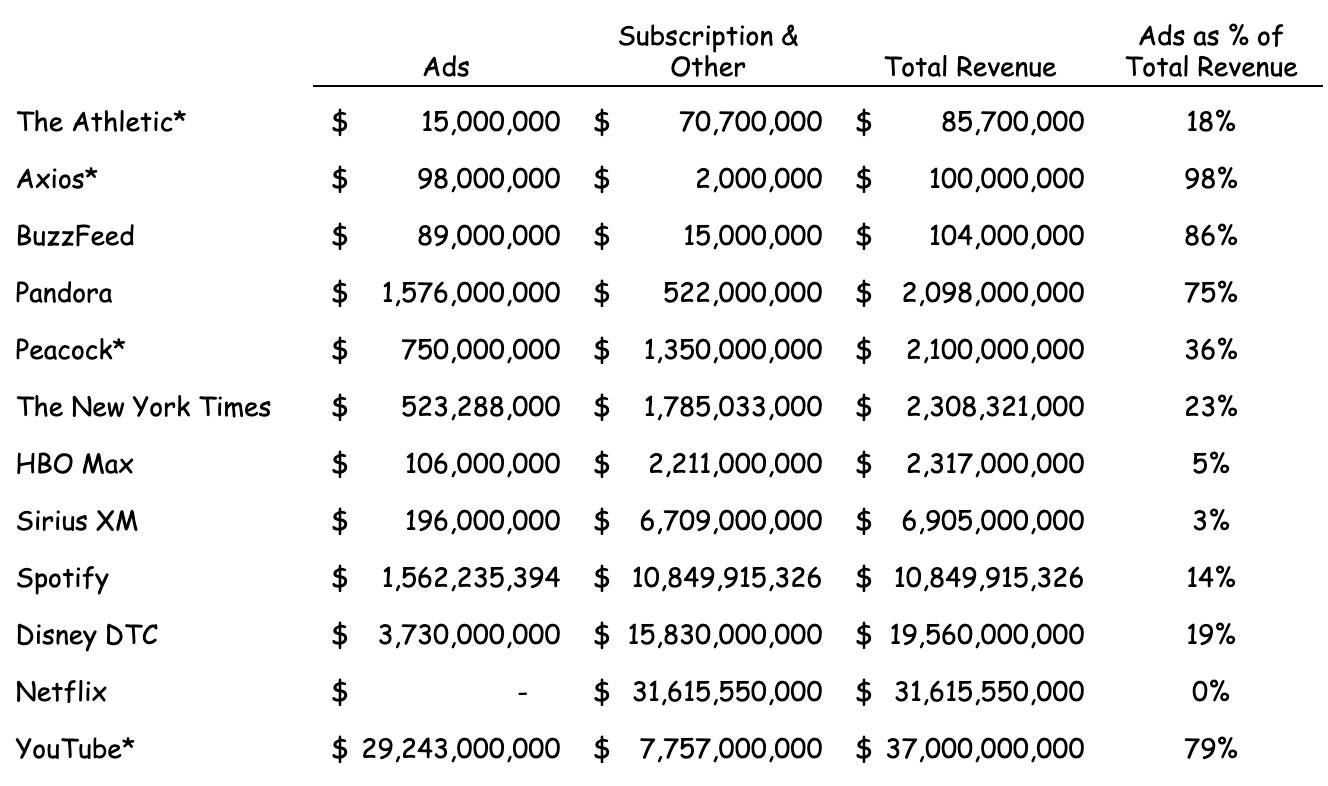

Below is a look at 2022 revenue for a grab bag of larger consumer businesses (excluding social media platforms1), segmented by advertising vs. subscription and other revenue. Asterisks indicate at least a partial estimate.

The table below shows the absolute 2022 revenue figures, and here’s a Google sheet with links, notes, and a few more notable consumer businesses.

It isn’t easy to find any consumer business that monetizes only with ads or only with subscriptions. Netflix may have been the last holdout: after decades as a subscription-only business and getting hammered by investor questions about ads every quarter, Netflix has finally launched a lower-priced, ad-supported tier.

If we can learn anything from the table above, perhaps we should expect the future of consumer businesses to mix subscriptions, advertising, and other revenue streams. And perhaps consumers will (already have?) come to expect the mixture of ads and subscriptions, just like we’ve seen in the past with magazines, newspapers, and cable TV.

But ads and subscriptions are fundamentally different business models, making it tricky to harmonize these revenue streams. Let’s first explore a few types of ads and their different characteristics.

Different types of ads

The potential upside with ads is that it allows you to make more money, sometimes without much (or any) additional effort. The potential downside with ads is that it usually harms the user experience.

With subscriptions, the goal is to deliver enough value to your audience so that they keep paying you. With advertising, you still need to deliver enough value to the audience so that they keep using your product. But compared to subscriptions, the incentives aren't as aligned — instead of being paid by your audience directly, you're selling your audience to advertisers. Your audience usually won't enjoy ads, but will tolerate them in exchange for sufficient value (especially if they're not giving up any cash).

Different types of ads vary widely in the degree to which it detracts from the user experience, how much you get paid, and how much effort is needed. Let's explore the two ends of the advertising spectrum: programmatic ads sold by an external platform, or direct sales where you sell your own ads.

Programmatic ads

Examples of programmatic ads would include monetizing YouTube videos via AdSense (i.e., ads sold by Alphabet); selling ads for your podcast through ad networks (e.g., Midroll); or selling ads in your newsletter through an ad platform (e.g., StackCommerce, Paved, or Swapstack).

The benefit here is clear: you make more money on stuff you’re already doing without lifting a finger. The downside is that programmatic ads tend to detract the most from the user experience. Comparatively, these ads tend to be less relevant to your audience, and usually don’t have any custom language around why you recommend the product. As such, programmatic ads are usually less effective, reducing how much you get paid.

Even within the world of programmatic ads, there's a wide range of quality, which impacts the benefits and risks. More niche ad platforms (e.g., programmatic ads for Finance newsletters) may be a better matchmaker for advertisers and publishers, supporting more effective ads and a better user experience, but may have less volume (e.g., lower ad inventory and fewer advertisers). On the flip side, massive ad platforms can have an abundant supply of advertisers and inventory. But matchmaking is more challenging, making it harder to manage the quality of the ad experience.

Direct sales

Direct sales include any effort where you work directly with the advertiser, with varying degrees of involvement. On one end, it can be a one-off ad buy where you provide a tailored ad to your audience in your newsletter, podcast, or YouTube video. On the other end, you may have an advertiser fully fund a new initiative, like a new YouTube channel, podcast season, or several editions of the newsletter.

If you sell your own ads, you have much more control over who you work with, making sure the sponsor makes sense for your audience and potentially tailoring the ad to your audience. These ads are usually more compelling and don’t detract from the user experience as much. At Crunchyroll, one of our best growth channels was creating ads directly with creators, many of which cared about Crunchyroll. Here’s an example of one of my favorites from Game Grumps:

Since the ad is usually much more relevant for your audience and you have a direct relationship with the sponsor, these types of opportunities usually demand a premium. (A lot of YouTube channels and creators make way more money on directly-sold sponsorships than programmatic ad revenue via AdSense.)

The main downside is that selling your own ads can take a ton of effort. It usually involves making a pitch deck, building relationships with potential sponsors, negotiating deals, delivering reports back to sponsors, and ensuring you get paid. In some cases, hiring someone or working with an agency to manage ad sales may make sense.

There’s also a more subtle risk with direct sales. Compared to programmatic ads, these ads can feel more like a strong endorsement, especially if the messaging is tailored to your audience. While this usually creates a better user experience and more effective ads, there’s some risk associated with lending your brand and reputation to the sponsor. No matter how much diligence you do, it’s impossible to know for certain that the sponsor is and will continue to be worthy of your endorsement (we saw this recently with FTX).

Hulu vs. Crunchyroll

To see how these two approaches to generating ad revenue play out at larger media companies, we can compare Hulu and Crunchyroll, where I spent most of my career.

Hulu started as a free, ad-supported video streaming service, where advertising was our only revenue stream. Buying video ads on the internet wasn't really a thing yet, so we had a large sales team to help convince advertisers to buy ads on Hulu. We positioned Hulu as a premium advertising opportunity, which helped us avoid lower-quality advertisers and a race-to-the-bottom dynamic. We also filled a lot of our inventory, which helped us tailor ads to the right audience and avoid ad fatigue (i.e., seeing the same ad repeatedly).

We invested a lot into building in-house ad tech (there wasn't any other option at the time!), attempting to create an ad experience that was better than cable TV for viewers and advertisers. We built ad products that allowed the viewer to choose the ad they watched, and decide between one long ad before a video or multiple ads during the video. We also spent a lot of time on the nuts and bolts: inserting ad breaks into videos, allowing for a dynamic number of ads per ad break, and fighting ad blockers.

Crunchyroll was toward the opposite end of the spectrum. We never had more than a few people working on ad sales, and most of our effort went toward selling tailored ad packages to a select group of advertisers. Most of our ad revenue came from external platforms selling video ads on our behalf (i.e., supply-side platforms). Our investment in ad tech was more constrained, and the advertising experience was more of an afterthought.

Compared to Hulu, Crunchyroll sold a much lower share of our total ad inventory and our advertising rates were a lot lower, ultimately leading to a much lower revenue-per-hour-watched for free subs. The free, ad-supported user experience was pretty rough, a sore spot within our broader product. But we generated quite a bit of ad revenue without incurring much cost or creating as much organizational tension.

The tricky part is there's no universally correct answer — both approaches have pros and cons. I wish we had invested a bit more in the ads experience at Crunchyroll, but our core focus was growing paid subscriptions, and we were busy trying to launch new products (e.g., VRV). For good reasons, improving our ads product was always tough to prioritize. At Hulu, our investment in the ads experience may have acted as a headwind against subscription growth. It was impossible given our ownership structure and circumstance, but had we been able to focus only on subscription growth, Hulu may have been more competitive with Netflix earlier on.

Ads and subscription cocktail

Mixing ads and subscriptions can introduce complexity, operational tension, and new risks related to the user experience. But when done well, monetizing via ads and subscriptions can lift a business toward a higher, more sustainable growth trajectory.

There are a few common ways businesses try to mix ads and subscriptions:

a free, ad-supported tier (e.g., Spotify, Crunchyroll)

a lower-priced, ad-supported subscription tier (e.g., Hulu, HBO Max, Disney+)

mixing ads into the subscription tiers (e.g., The New York Times)

Let’s explore some of the stuff we learned at Crunchyroll, a freemium service that has a free ad-supported tier with a deep catalog. Paid subscribers get access to new shows one week before free viewers (as well as ad-free viewing). But after that, nearly every show moves to the free, ad-supported tier forever. While I was at CR, there was a clear consumer appetite for the free, ad-supported tier, which accounted for roughly 75% of our total viewers.

For CR, the free tier provided a few key benefits. First, the free tier allowed us to monetize a group of users that were highly unlikely to pay for the service. We had a hell of a time competing against piracy sites. Also, compared to other streaming services, Crunchyroll had a younger-skewing, less-affluent audience. Our free, ad-supported tier allowed us to reach and monetize an audience that would otherwise resort to piracy sites (and not use CR).

Second, the free tier can be a meaningful growth channel for paid subscriptions. Compared to a hard paywall, where a user can't access any aspect of the product unless they enter payment info (e.g., Netflix), having a free tier can introduce you to a much broader audience, increase sharing and word-of-mouth growth, and allow new users to experience the product before forcing them to pay for anything.2

With the right balance of value between free and paid tiers, a large share of paid subscribers will start as free subscribers. When I was at Crunchyroll, roughly half of the new paid subscribers watched free ad-supported content before upgrading to a paid subscription. For Spotify, arguably the most effective freemium service, 60% of new paid subs come from the free tier.3

Introducing a free, ad-supported tier does add complexity. We now have to decide what free users get relative to paid subscribers, and we need to do so in a way that makes sense based on their respective customer lifetime values. Compared to paid subscribers, free users usually generate lower per-user economics (e.g., at CR, paid subs generated ~15x more revenue per month than free subs) and are harder to retain over time. If we tip too much value toward growing free viewers, we may take a hit on free-to-paid conversions, leading to a negative impact on revenue.

Deciding how to allocate value between free and paid subscribers can create organizational tension. The ads team usually wants more value allocated to the free tier, whereas the subscription team will want more value behind the paywall. Some healthy friction can be good, but it's another thing for the leadership team to manage (especially if it impacts incentives or compensation).

Similarly, ads and subscriptions take up distinct parts of the tech stack and have different considerations for optimizing the user experience. Managing ads and subscriptions within your product can split the attention of Product, Engineering, Marketing, and other teams. Netflix's singular focus on subscriptions (until recently) may be the main reason it's the largest subscription business ever, with over 230 million subscriptions.

Summary

Let's recap our journey:

It's possible to build large, sustainable businesses with only advertising or subscriptions. But many of today's most prominent consumer businesses are starting to mix advertising and subscription revenue (as well as events, merch, and other revenue).

There's a broad spectrum of types of advertising. How you approach generating ad revenue will impact the degree to which it detracts from the user experience, how much you get paid, and how much effort is needed.

Advertising and subscriptions are different business models, requiring different types of teams, tech, and tactics to grow. Because of the differences, mixing ads and subscriptions can create complexity, operational tension, and new risks related to the user experience. It's helpful to be aware of these friction points and tradeoffs.

I’m biased — my whole career has revolved around subscription products — but I’m a big fan of subscription-centric businesses, where subscriptions are 70% to 90% of total revenue. With that general revenue mix, I think businesses are usually more sustainable and tap into many of the benefits of ads without taking on too much extra risk or overhead.

Timing is also crucial. I would usually recommend introducing ads after the subscription product is in a rhythm of consistent growth. I would also encourage the team to think through and plan for the added complexity and new needs associated with advertising.

Of course, it’s impossible to make blanket statements. There are tons of large, sustainable advertising-only or advertising-centric businesses that are crushing it. When I was in the steaming world, we saw some amazing ads-centric businesses dabble in subscriptions when it mostly didn’t make sense, usually to appease executives or investors. Subscriptions don’t work in every situation, and the tail shouldn’t wag the dog.

Ok, that’s probably a good place to wind things down for now. I hope some of our learnings above help you decide what’s the best approach to monetization for your business.

I wrestled with this post quite a bit, so curious to hear what you think. What parts were intriguing or valuable? Where do you disagree? What does this makes you think about for your own business?

As always, thank you for reading,

Reid

Facebook, TikTok, Twitter, Snapchat, Pinterest, and Reddit are all mostly or entirely advertising-based businesses. There’s a good argument to be made that including YouTube means we should also include all these companies, but they still felt a bit distinct from others on the list. I included YouTube as I thought it was an interesting counter-example to Netflix. I also excluded Apple and Amazon for similar reasons. This isn’t a super rigorous exercise and should probably be viewed through that lens.

All of this is especially helpful early on, when most folks are unfamiliar with your product and why they need it. Letting new users gradually understand your value prop makes it easier to bring on new subs, reducing reliance on paid ads and reducing CAC.

From Spotify's F-1 filing: "Our Ad-Supported Service serves as a funnel, driving more than 60% of our total gross added Premium Subscribers since we began tracking this data in February 2014."

I’ve only worked in programmatic contexts and never had the right frameworks / vocabulary for talking about this stuff, so this post was extremely useful for me! I think you know where my priors are here: I’d love to be in a ~70% subscription / 30% “other revenue” world, with eg Meetings and direct sales / sponsorship type ad revenue helping expand the number of ways you can make money on Substack.

Very lucidly explained and presented man!

Great article. I wonder if comparing LTV between paying and “free” is right in a hybrid model. The LTV of a subscriber will be higher, but the absolute number is a fraction of the audience. I don’t understand extracting no value from people who aren’t paid subscribers. The complexity and tension is real, but that’s media. I just believe it’s common sense to make money in multiple ways and use ads as a reasonable value exchange with 90%+ of your audience.