How To Increase Your Price

Welcome to a fresh edition of Growth Croissant! 🚀 🥐

I’m Reid, your host on this journey. I’ve been lucky to be part of incredible teams that launched and grew some of the most well-known consumer subscription products: Hulu, Crunchyroll, HBO Max, and now Substack.

Growth Croissant will be an evolving home for our learnings, painful lessons, and frameworks for making hard decisions. My goal is to deliver you a comprehensive and actionable guidebook on how to grow your business.

Hello friends,

Increasing your price is one of the most immediate ways to boost earnings and customer lifetime value (“CLV”). But often entrepreneurs and leaders will go years without even considering a price increase, potentially leaving quite a bit of money on the table and under realizing their full earnings potential. Part of the reason is that increasing price is intimidating, delicate, and can easily backfire — it's crucial to nail the timing, messaging, and broader execution of a price increase.

The post below will focus only on raising the price of your core subscription product.1 We’ll cover how to know when it’s a good time to increase your price, how to gauge the impact of a price increase, and how to avoid common mistakes in executing a price increase.

Let’s dive in!

Should you raise your price?

The first step is to gauge whether now is an ideal time to increase your price. A great starting point is to check your health metrics, including:

Paid subscribers as a % of total subscribers (paid + free)

Free trial to paid conversion rate (if applicable)

Paid retention rates

Growth rate of new paid subscribers coming in

If these metrics are well above your peers, that’s great! But it could also indicate that your product may be underpriced and you may be leaving money on the table.

We recently met with a small team on Substack to review their health metrics. Roughly 40% of all their subscribers were paying, and they were retaining 85% to 90% of their subscribers after the first year — both extremely high. They had an ambition to grow their revenue, expand the team, and do more of what they were already doing, but better. As we discussed growth ideas, the most obvious was a thoughtful approach to increasing price, including what existing subscribers were paying.

Often, when we tell entrepreneurs or leaders that their health metrics are above-average, they feel reassured and tune out. But it’s important to realize this may also be a strong signal that your price is too low, and you may not be realizing your full earnings potential.

Another important consideration is how a price increase relates to your priorities. Businesses will regularly rotate between prioritizing growth and profitability. All else equal, raising prices will make it harder to bring in new subscribers, which can have a ripple effect and limit audience growth. If you’re early in your business journey or focused on subscriber growth, it may not be the best time to increase your price.

Conversely, raising prices can be the most effective growth strategy for a mature business with stable subscriber growth. A good example is Netflix's domestic business (US + Canada), where subscriber growth has been virtually flat since a COVID-induced surge in early 2020. As paid subscriber growth has stalled, Netflix has consistently relied on price increases to drive continued revenue growth.2

Once you decide the moment is right for a price increase, consider any upcoming initiatives to fine-tune your precise timing. If you’re about to launch a new feature or anticipate a meaningful improvement to your value proposition, announcing a price increase with those changes can help land the messaging and increase the odds of more subscribers sticking around after their price goes up.

Gauging the impact of a price increase

Two things that tend to surprise people about price increases:

Most of the revenue lift from a price increase comes from existing subscribers. Finding a thoughtful way to increase what existing subscribers are paying is key to realizing the value of a price increase.

A price increase impacts subscriber acquisition much more than subscriber retention. After a price increase, it’s most likely that new paid subscriber growth will slow down, whereas retention rates will be stable.

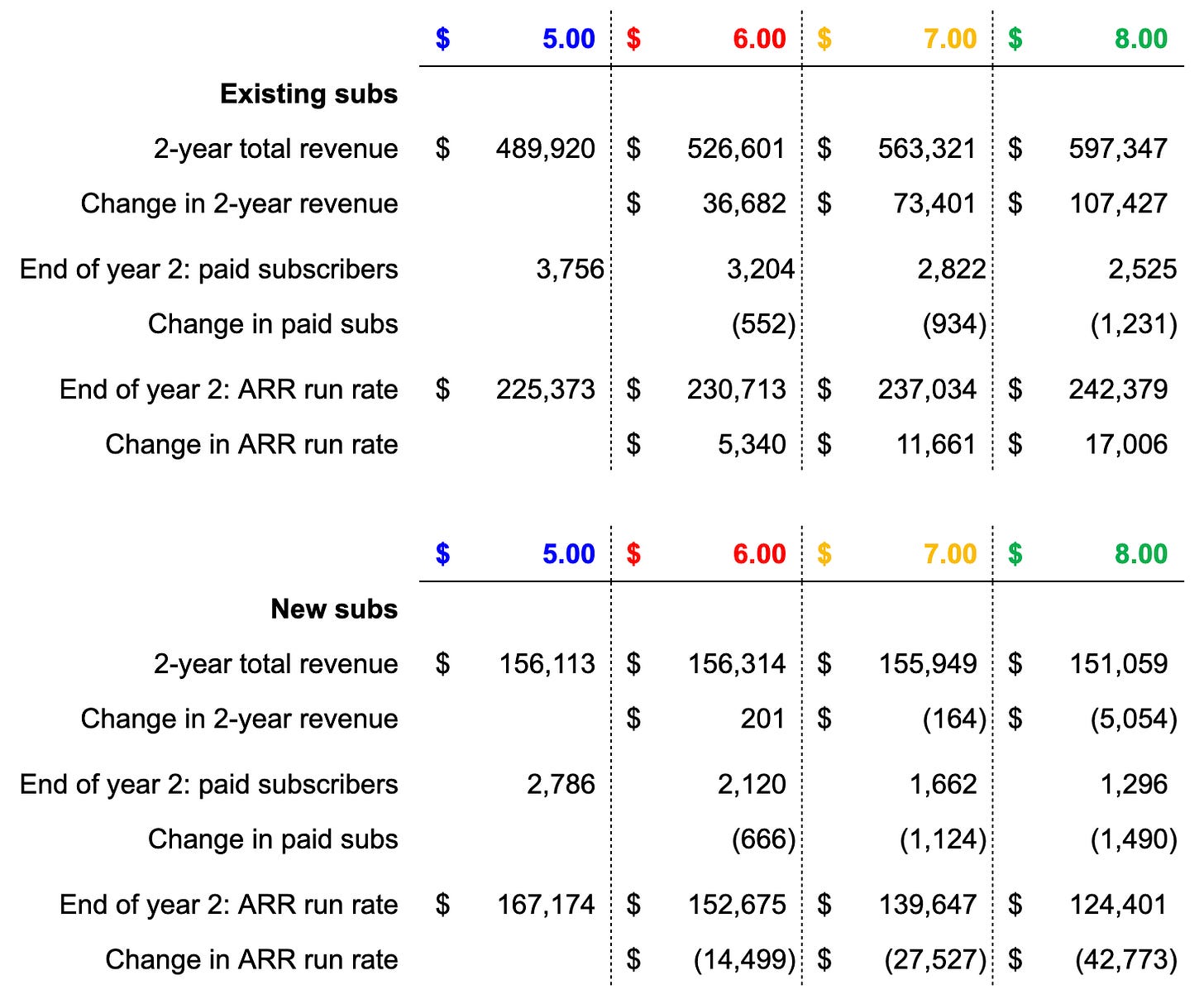

Let’s go through a hypothetical example to give you a framework for gauging the impact of a price increase. We’ll imagine having 5,000 subscribers paying $5 per month ($300,000 in annual recurring revenue; “ARR”3), and we’re considering raising the price to $6, $7, or $8 per month.

We’ll start with how a price increase impacts existing paid subscribers, then cover how it impacts the inflow of future new paid subscribers. (Here’s a Google Sheet if you want to follow along.)

Impact on existing subscribers

Without any material change to our product or value proposition, the more we increase the price, the more we can expect retention to worsen. In the image below, compared to the status quo (i.e., no price increase), we see worse retention if we increase the price to $6, but much worse retention if we increase the price to $8.

With no price increase, we expect to keep 75% of our paying subscribers two years later (3,750 out of the starting 5,000). If we raise our price to $6, we end up with 3,200, losing an additional 550 subscribers; if we increase the price to $8, we lose 1,200 subscribers.

As shown below, even with worse retention in our three price hike scenarios, our per-subscriber and overall earnings during the first two years are still higher. But the drop in paid subscribers severely limits future revenue growth. If you press a price increase too far, even if the near-term gains are compelling, those gains can quickly vanish if you end up on a lower long-term revenue trajectory.

Impact on future subscribers

While a price increase is unlikely to change retention for new subscribers, it will slow down the inflow of new subscribers.4 The more we increase the price, the more we can expect new paid subscribers to slow down.

Let’s assume we’re adding ~100 new paid subscribers per month. We’re growing fast and expect to maintain a monthly growth rate of 4% for the next two years (~160 new subs per month). With no price increase, we expect to add 2,800 net new subscribers in two years, equating to an additional $167,000 in ARR.

If we increase the price to $6, let’s say our monthly growth rate slows to 2.0% — we only add 125 new subs per month (vs. 160 status quo) and end up with ~670 fewer paid subscribers. With a significant price increase (e.g., $5 to $8), it’s possible our growth flips negative and we actually see retraction (-2% vs. +4% status quo), leading to a substantial drop in paid subscribers (1,500 fewer paid subscribers).

The slowdown in new paid subs doesn’t impact the near-term earnings as much — all the scenarios have roughly the same revenue during the two years after a price increase (bottom two rows in the table above). But all the scenarios lead to substantial drops in paid subscribers, limiting our long-term growth trajectory. As a proxy for our momentum, here’s a chart showing paid subscribers and our ARR run rate two years after the price increase:

Bringing the pieces together

Now we can combine our expected impact on existing and future subscribers to understand what could happen after a price increase.5 While the numbers are made up, I did want to show that it’s pretty common for a price increase to yield near-term revenue gains, but that usually comes at the expense of paid subscriber growth.

Finding the right balance between near-term earnings boost and long-term paid subscriber growth is crucial. The extra revenue from a well-executed price increase can be hugely beneficial. But when pressed too far or mishandled, the slowdown in new subscribers and the downward pressure on retention can be a severe headwind on subscriber growth.

How to raise prices

While Netflix has sunk into a regular rhythm of price increases, their first price increase didn’t go so well. It would become known as the Qwikster debacle — a fumbled attempt to navigate the transition from mailing DVDs to streaming video. The business decisions were sound, but the comms and execution were deeply flawed. After the pricing mishap, Netflix’s brand took a severe hit and its stock sank 83% in four months.

Increasing the price for existing subscribers is extremely delicate — nailing the messaging and framing is essential. To start, make sure you’re being transparent. At a minimum, make sure you're being explicit in letting subscribers know when their price will change and by how much.

When you inform subscribers about the price increase, it’s usually best to avoid making excuses, pointing to things like currency fluctuations or increased costs as the reason for increasing the price. Instead, it can be valuable to remind subscribers how much the product has improved and announce any notable upcoming changes. You can also reference what the additional funding will enable you to do, including just more of what you’re already doing, but better.

For the next few price increases following the Qwikster debacle, Netflix let existing subscribers pay the same rate for a while after the price increase. Netflix has moved away from this approach, instead raising prices for existing and new subscribers simultaneously. But if you’re going through your first or second price increase, showing a little love to your existing subscribers can go a long way to reducing any risk of churn or hit to your brand.

Let’s wrap up with a few other best practices for executing a price increase:

Gradual price increases are way better than larger price increases. Netflix and Spotify have never increased prices by more than $2 at once, instead opting for a series of gradual price increases.

Price increases should be very infrequent. It depends on various factors, but once every 2-3 years is a good starting point.

It’s awkward to raise prices and then lower them again. Of course, offering the occasional discount or special offer can be valuable. But try to be confident and firm in raising your “retail” price.

Summary

I've seen several products improve significantly without any price adjustment. Increasing prices can be intimidating, and rightfully so — it's tough to get right and can easily backfire. But choosing not to increase prices is a decision as well, one that often leaves a lot of money on the table and the business on a lower growth trajectory.

It's important to periodically evaluate whether it's a good time to adjust your price. If the time is right, a well-executed price increase will give you extra funds to invest in the business, placing you on a higher, long-term revenue trajectory.

That's all we got for now — what are your takeaways? Have you ever thought about increasing your prices? If so, what's held you back from doing it?

As always, thank you for reading,

Reid

A few other pricing-related topics we may cover in future Croissant posts:

Setting your core price.

How much to discount annual plans against your monthly price.

Using higher-priced tiers (for your most passionate customers) to increase revenue per subscriber (“ARPU”).

Using lower-priced tiers (for casual users) to maximize paid subscribers and revenue.

Charging more or less in certain countries.

Driving paid subscribers with discounts, special offers, and marketing campaigns.

Netflix's attempt to increase revenue per membership as membership growth slows has been a long-term effort, and they've been quite successful. I only highlighted the past few years as the slowdown in membership has been more pronounced.

5,000 paid subs x $5 monthly ARPU x 12 months = $300,000 in ARR.

This can be a little counterintuitive. After a price increase, any new subscriber is agreeing to pay the higher price when they join. While that will lower the number of people joining, it won’t really impact their paid retention after they join.

Many readers respond to posts via email with some incredibly valuable comments and hot takes, and I always wish they were comments on the post.

The below is from one my best friends, who agreed to let me share it on the post (and copying over to Notes too). Here's what he said:

...

I have (slight) beef with a few points you make here:

1) You sort of omitted the concept of consumer surplus. I think that's a critical factor in assessing a price increase. How does time spent compare to value? How does time spent : value compare to my peers?

2) You make the point that growth will slow or will likely slow with a price increase. Not always. There is a value perception. Sometimes you can increase the price and the perception of your product goes up and you sell more. I think there are probably some examples in the cosmetics or luxury goods space.

3) I wouldn't necessarily include it here but I think there is a decent discussion around increasing price while introducing a plan and using one of them as a bit of a red herring to stimulate growth on the other. Simple example: I currently have two plans. One is Free and the other is 10 articles per month for $10. In the future, I'm going to have three plans: Free, 5 articles per month, and 10 articles per month (+1 phone call with me). My new prices are free, $10 per month, and $15 per month. I just executed a price increase but in a pretty elegant way that might stimulate more growth.

4) You make the point that "the more we increase the price, the more we can expect retention to worsen." Maybe. Especially without a grandfathering strategy. BUT, if I raise prices and tell my current subs you're good for a year that might help retention. Also, if I tell new subs the price is going up in a quarter so hurry that might help growth.

Mostly these points are nuance and I think you're right to stick to the big picture. The one I'd fight for a bit is the first one. I think it deserves to be there because I do think it's an important consideration. Another good post : )

Great post, on a very important topic. I love that you included the Google Sheet!

My 2 cts: price increases don't always have to be for existing subscribers, it's ok to grandfather people in if projections and tests don't look good. If they're just for new subscribers, then it's ok to do them more frequently