Building a CLV Model for Ad-Based Businesses

Hello friends,

In our last post, we explored the pros and cons of different types of ads and how to think about mixing ads and subscriptions.

We had a few folks respond with questions about how to model customer lifetime value ("CLV") for ads-based businesses. Like our CLV model for paid subscriptions, we can use an ads-based CLV model to make strategic decisions:

How much to invest in bringing on new subscribers to an ad-supported tier?

How to allocate value between the free and paid tiers?

How do we balance efforts geared toward driving advertising revenue vs. subscription revenue?

Let's bring back our friend Big Dean ("BD"), the (hypothetical) sole operator of the prosperous newsletter Big Dean's Boardwalk Wings. BD has grown the email list to 20,000 subscribers and has nurtured an engaged, niche audience of craft beer enthusiasts and aspiring at-home chefs. While paid subscription growth is going well, Big Dean starts to wonder whether he could monetize his large free audience through sponsorships in his newsletter. To help Big Dean understand the opportunity, let's help him build a CLV model based on advertising (link to CLV model in Google Sheets).

Ad-based subscriber economics

Like our CLV model based on subscriptions, our first step is to get a sense of how much money we earn through advertising for each subscriber.

Big Dean starts by creating a sales deck for his newsletter, tailored to a select group of advertisers: companies that sell home beer-brewing kits, air fryers, and hot sauce subscription boxes. He highlights the growth of his newsletter and emphasizes how unique and compelling his audience is to his target advertisers. BD also calls out how many of his posts get even wider exposure on Twitter, TikTok, and Instagram. He also shows that his posts have a long shelf-life, generating a solid stream of views beyond the initial email.

After doing some light research and asking friends that sell sponsorships in their newsletters, Big Dean chips away at determining his ad inventory and pricing. He doesn't want to clutter his newsletter with ads, so he limits his inventory to one "presenting sponsor" per newsletter post. The presenting sponsor will have a dedicated section at the top of the newsletter, including their logo and up to a 120-word pitch for their product.

Pricing proves to be especially tricky. Some of BD's friends charge a flat fee per post, others only sell monthly packages, while others have incentive-based pricing (e.g., cost per click, revenue share on purchases via a unique URL). Most of the folks he talks to price their ad inventory based on every 1,000 unique emails opened ("CPM"). But still, there's a broad spectrum of rates: some charge a $30 CPM, while others charge up to $200(!) CPM.1

Big Dean doesn't want to undersell his inventory, so he starts by asking for a $100 CPM. He usually has a 50% open rate: out of his 20,000 total subscribers, about 10,000 unique recipients open each post. With a $100 CPM, he expects to make $1,000 in ad revenue for each post. Big Dean sends about ten emails each month, which should generate roughly $10,000 in monthly ad revenue.

On average, each subscriber opens five emails per month.2 If we multiply that by our earnings per unique email open — $100 per 1,000 unique opens, or $0.10 per unique open — Big Dean earns $0.50 per free subscriber each month.

Engagement-based retention

With paid subscriptions, we want to know how long someone will remain a paying subscriber before they cancel. As discussed in previous posts, paying subscribers are most likely to cancel earlier in their subscription, and the likelihood of canceling decreases rapidly the longer someone stays subscribed. In other words, the probability that a paying subscriber will cancel decreases exponentially, not linearly, over time.

With advertising, since revenue is intertwined with engagement, there are two elements of retention:

What share of subscribers remain on the email list (i.e., they do not choose to unsubscribe)?

What share of subscribers remain active?

Like the decay curve for paid subs, the likelihood that a free subscriber remains on the email list and continues to be active follows an exponential decay curve except for the first month, where we see a step-function decrease. When we worked with advertising-based newsletters at Yem, we would typically see ~10% of new subscribers choose to unsubscribe in the first month. We would also see another 10% to 15% that never engaged in any way in the first few months, with very few engaging after that. On the flip side, if a subscriber is active after the first month or so, longer-term retention is usually quite strong. There was a high probability those subs would remain on the email list and continue to be active far into the future.

Let's assume Big Dean's retention follows a similar trend. The image below shows how many of BD's subscribers remain on the email list after two years (i.e., those that do not unsubscribe) and how many are still actively engaging with the newsletter.

Bringing it together

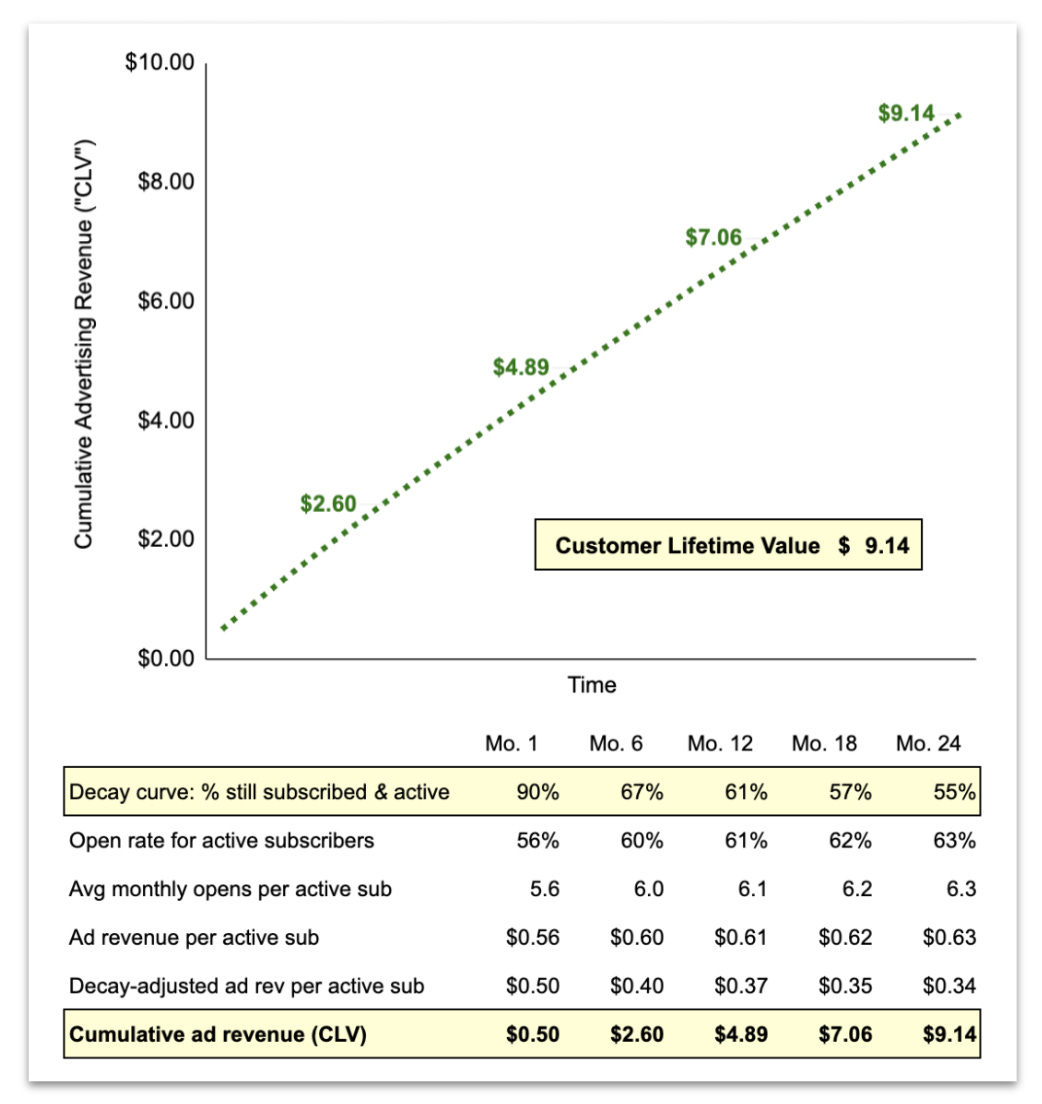

To form our CLV forecast, we want to combine our ad-based subscriber economics and retention (i.e., what share of subs remain on the email list and active). Based on Big Dean’s assumptions for pricing (e.g., $0.10 for each unique email opened) and retention, below is a look at how much advertising revenue we expect to earn over two years from each subscriber.

While we’re here, let’s highlight one key difference between advertising and subscriptions. In nearly every case, advertising revenue is based on engagement, either directly (e.g., cost per open or click) or indirectly (e.g., flat fee based on expected engagement). As such, having less-engaged or dormant subscribers choose to unsubscribe has little to no impact on advertising revenue. Paid subscriptions are quite different: we lose the same amount regardless of each paid sub’s engagement.3

Finding balance

As we covered in our last post, most consumer products mix advertising and subscription revenue. But these two revenue streams have fundamental differences, and how you prioritize one over the other will shape your company’s identity. It’s valuable to have a sense of your desired revenue split to help you make strategic decisions that drive you toward your target.

Big Dean wants to be a subscription-centric business, aiming for 80% of his revenue to come from subscriptions. In other words, for every $4 in subscription revenue, he wants to earn $1 in advertising revenue.

With a better understanding of how much BD earns from each subscriber through advertising and subscription over time, we can correctly balance those two revenue streams. Let’s start by comparing how much we earn (i.e., per-subscriber economics) from each paid subscriber vs. free, ad-supported subscriber.

Not surprisingly, subscriptions generate a lot more cash than advertising on a per-subscriber basis. But we also want to factor in retention and how much we expect to earn over time (i.e., CLV). Compared to getting paid subscribers to fork over their hard-earned cash over time, we may find it easier to keep free subs engaged. We also expect most of our audience will never pay and remain free ad-supported subs, which we need to factor in as we think about our total revenue mix.

The summary table below brings all the pieces together. From above, BD earns ~17x more cash per subscriber through subscriptions than advertising. After factoring in retention, BD earns 12x more cash per subscriber through subscriptions than advertising during the first two years.

We can adjust our CLV (a per-subscriber metric) based on audience share to gauge our total revenue mix. Currently, 75% of BD’s email list are free subscribers — for every paid subscriber, there are three free, ad-supported subscribers. After adjusting CLV based on audience share, we expect paid subscriptions to drive 4x more total revenue than advertising, which maps nicely to BD’s desired revenue mix (80% subscription vs. 20% advertising).

If we find ourselves in this position, we can feel more confident that we’re adequately balancing the two revenue streams. But if we start to tip too far in one direction, we can fine-tune our revenue mix by adjusting a few strategic levers:

Keeping the right balance of value provided to paid vs. free subscribers:

If we provide too much value to paid subscribers, we cut off our top-of-funnel audience growth and under-monetize our casual, lower-intent subscribers.

If we provide too much value to free subscribers, we may suppress our paid subscription growth, which will always have better per-subscriber economics and CLV.

For larger businesses, investing the right amount in supporting the free and paid tiers:

Making sure the two different product experiences are getting enough love.

Managing intra-company tension between teams (e.g., teams dedicated to growing ad revenue vs. subscription revenue).

Helping various teams focus and prioritize their efforts.

Summary

So much of what we discuss in the Croissant is about finding balance and harmony. Managing your revenue mix is no exception.

You are what you eat — a company’s revenue mix significantly impacts its identity. Many businesses have fallen off the rails chasing revenue or whimsically prioritizing different revenue-related initiatives. While all the above can be a bit academic (especially if your business is just getting started), it can be valuable to have a goal for your business model and to make conscious decisions that drive toward your desired revenue mix.

Of course, goals shouldn’t be written in stone — it’s also important to change course based on what you learn along the way. But having a desired revenue mix can provide guardrails for how you operate and go a long way to focusing your (or your team’s) attention.

That’s a good place to wrap things up — I’m curious to hear what you think. What parts were valuable, and what parts dragged? What open questions do you still have?

As always, thank you for reading,

Reid

Part of the reason there's a wide spread on sponsorships is because it depends on a wide variety of factors.

As we've pointed out, averages are dangerous. From our paid ads post, there are cases where a similarly sized segment of subscribers open every single email (i.e., your 100% open rate club) and never open any email (i.e., dormant subscribers).

That said, we usually see engagement correlate with paid retention.

Fantastic work!

Are your images made with AI? I love them!