Hey team,

We’ve reached our third post in a series covering the most important metric for any business: customer lifetime value. Our first post defined customer lifetime value ("CLV"), and our second post walked us through the key drivers of CLV — if you missed either of those posts, it might help to check them out before jumping into the one below.

Now that we have a solid conceptual foundation, let's dive into a CLV model. To guide us, we'll build a CLV model for a hypothetical newsletter: Big Dean's Boardwalk Wings — a weekly exploration of innovative wing recipes.

Here is a CLV model in Google Sheets — feel free to make a copy or share it with others. The post below will walk through the "Per-sub Money Stuff" tab, which will help us discover how much take-home cash we make every time a subscriber pays us — we’ll call this "per-subscriber economics" or “subscriber economics”. We’ll also cover a few ways we can use subscriber economics for early decision-making.

For simplicity, we’ll focus on monthly paid subscribers but will eventually come back to factoring in annual subscribers.

Subscriber economics

Let's assume Big Dean's charges $10 per month, of which we pay 10% in platform costs (e.g., Substack) and 6% in payment processing fees (e.g., Stripe). After paying our variable costs — $1.59, or 16% of our revenue — Big Dean's earns $8.41 per sub per month in contribution profit. In other words, for every additional paid subscriber we add, we make an extra $8.41 in cash per month (as long as they remain a subscriber).

Now that we know how much take-home cash we'll earn for each subscriber, we can start to do some napkin math around important decisions. For example, we can explore when we break even on different levels of investment or gauge the most feasible combination of paid subscribers and price to reach a specific earnings target.

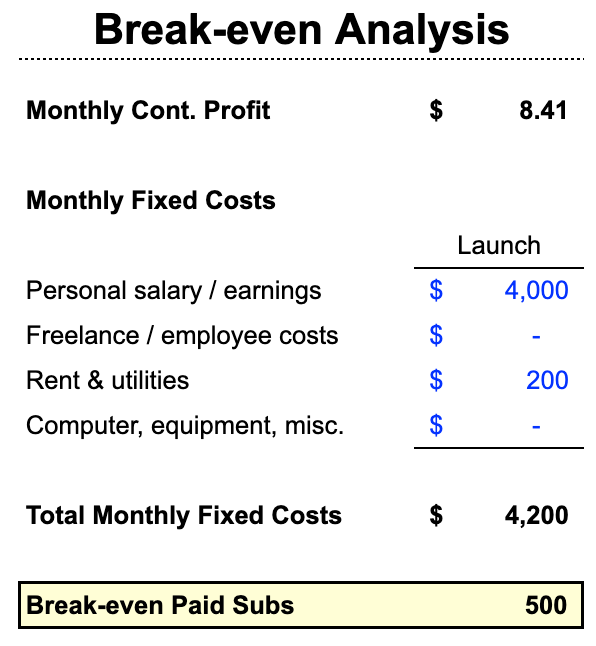

Break-even analysis

Early on, Big Dean — the sole operator of Big Dean's Boardwalk Wings — needs $4,000 in monthly earnings to cover his living costs and make this worth his time. He quickly discovers it's impossible to focus on writing in his restaurant, so he rents a shared co-working space for $200 per month, bringing his monthly costs to $4,200. At this level of fixed costs each month, Big Dean would need about 500 paying subscribers to break even ($4,200 fixed costs / $8.41 earnings per subscriber).1

We can also explore our break-even point at various levels of investment. Let's assume things are going well for Big Dean: he has found his audience and settled into a rhythm of publishing each week. There's a solid inflow of new paid subs, and he's doing a great job retaining existing paid subs. Our faithful protagonist won't admit it, but he's having a hard time keeping up with the newsletter's expanding demands (and opportunities!). He could use some help building their audience on social; developing relationships with other restauranteurs, sponsors, and other partnerships; and working on various tasks that would elevate the quality of their content.

Big Dean grabs a napkin and starts to etch out a "growth" scenario where he would bring on a generalist to help run the newsletter. Factoring in the cost of hiring someone and a little more take-home earnings for himself, Big Dean estimates that his fixed costs would rise to ~$10,000 per month — all else equal, Big Dean would need 1,200 paying subscribers to break even. It actually seems reasonable; encouraged by this discovery, Big Dean sketches out an ideal longer-term "steady-state" scenario where he would have a team of folks specializing in specific tasks (e.g., Editor, Marketing, Sales). With a few people on the team, he guesses that costs would go up to $20,000 per month. At this level of spend, they would need 2,500 subscribers to break even — while this feels like a distant mountaintop at the moment, it helps crystallize a longer-term goal for Big Dean2.

Choosing your pathway

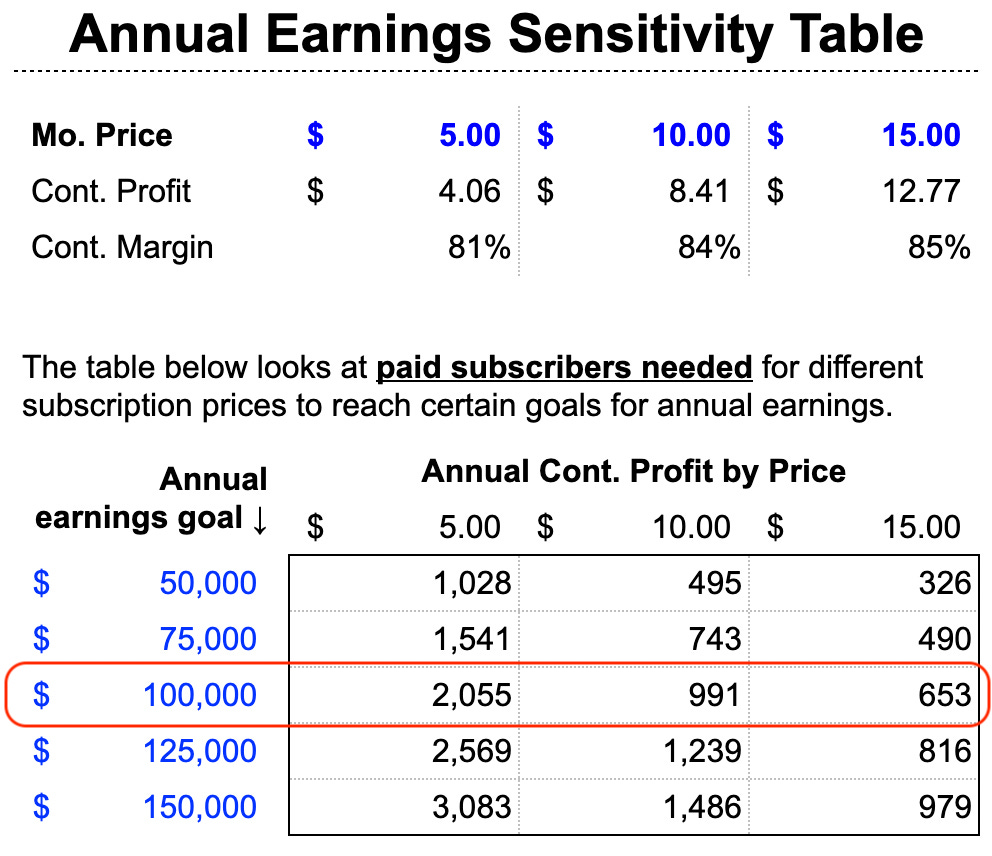

We can also explore our earnings at different levels of paid subscribers and subscription prices, which can be especially helpful if we have yet to launch and are considering different prices.

Let's imagine we want to get to $100,000 in annual earnings, and we're considering pricing our product between $5 to $15 per month.

From our napkin math, to reach $100,000 in annual earnings, we would need the following:

2,055 paid subscribers at $5 / month

991 paid subscribers at $10 / month

653 paid subscribers at $15 / month

Now we can gut-check which of these pathways seems most reasonable, considering our audience's willingness to pay for our product and the size of our potential audience. For example, if you feel your audience may be a bit more niche than usual, but you'll be able to provide substantial value to them, it may be better to price a bit higher.

Payment processing fees

For each successful transaction, Stripe charges 2.9% of the amount paid plus a flat $0.30 fee. An often overlooked byproduct of Stripe's pricing: the $0.30 fixed fee becomes more taxing at lower amounts paid. For $5 transactions, Stripe's fee is close to 9%; at $10, Stripe's fee drops to 6%. In other words, you would have more cash in your pocket if you charged one person $10 rather than two people $5 each. Stripe's fee structure is also part of why annual subscriptions can generate more long-term revenue than monthly subscriptions.

You probably shouldn't let payment fees become a significant factor in determining how much you charge or take it as a reason to drive people toward annual subscriptions, especially if you’re just getting going. But it’s a useful example of how variable costs can impact your subscriber economics and take-home earnings.

Many entrepreneurs, execs, and investors make misguided decisions based on the assumption that their revenue is roughly the cash they take home. Now that we're familiar with subscriber economics, we can sidestep this common pitfall and feel more confident in making important decisions.

I'd love to hear what you think in the comments or by replying to this email. How does a better understanding of subscriber economics impact your decision-making? What past decision would you like to revisit? What follow-up questions do you have, or areas we should further explore?

Tune in next week when we cover subscriber decay curves and customer lifetime.

Thanks for reading,

Reid

PS — for the inspired, feel free to jump ahead in the CLV model and reach out with any questions.

It's worth noting that Big Dean would need to maintain this many subscribers to keep covering his fixed costs. If he reached 500 paying subscribers, then fell back to 450 paying subscribers, Big Dean would no longer be covering his fixed costs. The way we used to think about this in the streaming world: we needed an average balance of X paying subscribers to pay $Y in fixed costs.

There’s a slightly more sophisticated way to forecast paid subscribers and, as an extension, cash flow over time — something we’ll return to in a future post.

As an aside, larger media companies can do the same type of napkin math. Let's say Netflix expects its annual content spend to stabilize at $50 billion (or ~$4 billion per month). Through price adjustments (and finally cracking down on account sharing), Netflix also thinks it can inch its contribution margin per subscriber to $15 per month. Netflix would need about 267 million paying subscribers to cover its content costs (not to mention all its other fixed costs).

thanks for this. for my newsletter I end up taking just over 85% net after stripe/substack/refunds. I have a higher price point 15/168, and have a decent % of annual subs. When I run special offers I usually limit the discounts to annual subs only, as I want the one time charge, more cash upfront, and when renewal hits after 12 months at the non-discounted rate you get a nice bump.

This is pretty detailed and understandable. Thank you for writing Growth Croissant. I'm binge reading forward from the archives right now, and am looking forward to reading more about what initially attracts customers, and how to maintain them.